Facebook’s drones – made in Britain

In a warehouse in Somerset, the latest phase in Facebook’s bid for world domination has been taking shape.

Or, to put it less dramatically, the social network’s plan to connect millions in developing countries is proceeding.

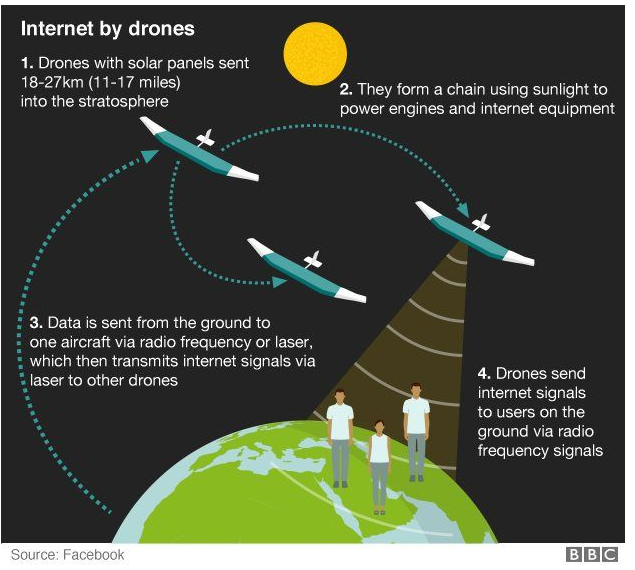

It is called Project Aquila and involves building solar-powered aircraft which will fly for months at a time above remote places, beaming down an internet connection.

Two years ago Facebook bought small British business Ascenta, which specialises in solar-powered drones, and its owner Andy Cox is now the engineer running Project Aquila.

At the end of June, the first aircraft produced in that warehouse on an industrial estate in Bridgwater was dismantled and taken in pieces to Arizona. There, it was reassembled for its first flight.

The unmanned aircraft, which has the wingspan of a Boeing 737 but is only a third the weight of a typical family car, stayed airborne for 90 minutes and performed well. The fragile structure did suffer some damage when it landed in a stony field some way short of the runway.

When it finally goes into service the idea is that it will come to rest on grassland.

Back in Bridgwater after the flight, Mr Cox told me there was still a long way to go.

“Eventually we will fly at 60,000-90,000 feet, above conventional air traffic, where it’s very cold, and for periods of up to three months,” he said.

“That means we can loiter around a given waypoint providing the internet without interfering with other traffic.”

Right now the record for continuous flight by a solar-powered aircraft is two weeks, so getting to the point where the Facebook drone can stay airborne for three months will involve a lot more work.

Solar cells must be embedded all over the upper surface of the aircraft, while keeping it as aerodynamic and light as possible.

He lifted up one section to show just how light the structure was. “It needs to be light. Every kilo of extra weight means we need more power to fly it.”

During the day, the plane will fly on solar power, replenishing the batteries that keep it powered at night. They account for about half of the weight of the aircraft.

This might sound like just the kind of fringe project that a hugely wealthy technology business can afford to tinker with, but Facebook seems to be taking it seriously at the highest level. Mark Zuckerberg was in Arizona to see the first flight, and the global head of engineering, Jay Parikh, has been making frequent trips to Somerset to oversee progress.

“Our mission is to connect everyone on the planet,” Mr Parikh told me, explaining that Project Aquila was just one of a number of technologies Facebook is developing to bring connectivity to remote places.

He ducked my question about what was the return for Facebook shareholders, insisting that the aim was just to help the telecoms industry bring down the cost of connectivity. Facebook, which has 1.6 billion active users, reckons there are another 1.6 billion people out there in need of an internet connection.

Of course, it is not alone in its mission to get these people online. Google’s Project Loon involves using high altitude balloons to connect people to the internet in the same remote places that Facebook aims to serve. Both of these internet giants would like to be seen as benevolent forces advancing the global good of connectivity, so we can expect the race to be pretty fierce.

And these kind of initiatives are not without controversy. India rejected the Facebook Free Basics project, which was to give citizens limited, free web access via their mobile phones, amid suspicions that it was all about making the company more powerful.

This time, Facebook is treading carefully with Project Aquila, emphasising that it will just provide the connection, leaving local companies responsible for any services.

Mr Zuckerberg seems to have a genuine desire to bring people the connectivity that could transform their lives. But you cannot help feeling that he will also be hoping that Facebook’s drones will be flying above sub-Saharan Africa before Google’s balloons.

http://www.bbc.com/news/technology-36855168