Virtual Reality Is Coming to Medical Imaging

The medical-imaging industry is about to get a lot more “real.”

New technologies coming to some hospitals and medical schools will allow doctors not only to see three-dimensional pictures produced by imaging equipment such as magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound, but to interact with what is pictured—say, a heart or liver—as if it were real. Using devices such as virtual-reality viewers, as well as styluses or other hardware that provides a feeling of resistance, doctors will be able to take a tour of a patient’s brain, for example, and even cut into virtual tissue.

Most medical-imaging equipment on the market today can generate 3-D images. Yet surgeons often stick with what they were taught to do in medical school, which is view multiple two-dimensional snapshots of the body part on which they plan to operate and reconstruct a three-dimensional view of it in their heads. Many of them don’t think 3-D images offer enough increased benefit to merit that becoming the new standard, and the higher cost of 3-D imaging means hospitals have to demonstrate it actually improves patient care to get reimbursed.

That may be about to get easier. New virtual-reality technologies, which can pull in imagery and data from multiple sources, have the potential to more dramatically affect patient outcomes. In clinical trials, some virtual-reality simulations reduced surgical planning time by 40% and increased surgical accuracy by 10%.

“VR gives a very immersive way of looking at all this data,” saysSandeep Gupta, manager of Biomedical Image Analysis at GE Global Research, a division of General Electric Co., which is working to integrate virtual reality into its existing imaging equipment. “Doctors may be able to see which brain regions are affected by a neurodegenerative disease, for example, or which neural pathways information and signals are flowing through.”

The new technologies come in a variety of forms, from fully immersive virtual-reality studios (which could be useful for training in medical schools) to simulations that use virtual-reality viewers such as the Rift headset from Oculus VR LLC. GE is working with a handful of research hospitals on early-stage testing of technology that will allow a doctor wearing a Rift headset to take a virtual tour of a patient’s brain, and perhaps even determine how surgery might affect various parts of it.

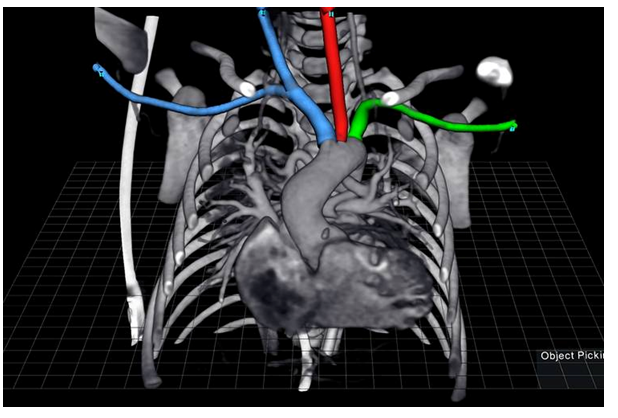

Elsewhere, pediatric surgeons at Stanford University Medical Center have used a virtual-reality platform from EchoPixel Inc., a Mountain View, Calif., startup, to plan surgeries on newborns missing pulmonary arteries. It’s a difficult surgery that requires precise mapping of pulmonary vessels, typically done using pen and paper.

Using the technology, surgeons and radiologists were able to develop more accurate surgical plans in 40% less time, says Frandics Chan,who led the Stanford trial. It also changed the radiologists’ role. “They become more involved in treatment planning by taking their understanding of the disease and preparing the data sets for the surgeon to visualize,” said Dr. Chan while presenting his findings at a conference of the Radiological Society of North America in December 2013.

One of the most promising uses of virtual reality may be in medical training. Universities that can’t afford to store cadavers for teaching may be able to rely on virtual reality instead. “Virtual reality has a clear advantage there because you can see a true 3-D body, and you can even practice on it because there’s full feedback,” says Bin Chen, a researcher at Purdue University who has studied the use of virtual-reality technologies in medical settings.

Still, widespread adoption of virtual-reality technology is probably several years away. “Medical professionals don’t want to change quickly, and that’s probably a good thing,” says Mr. Chen. “They want to make decisions slowly and reliably.”

http://www.wsj.com/articles/virtual-reality-is-coming-to-medical-imaging-1455592257